SOLVING THE COSTUME PUZZLE - BY JENNIVER SPARANO

“You’re a costume designer? You must be so creative!”

I hear this phrase – or variations of it – pretty regularly. I’ve designed costumes for 45 years, and for most of those years, I’ve also worked for KeyBank. So when my bank co-workers learn that I have a second career designing and sewing theatre costumes, they assume that I’m conjuring elaborate, glittering costumes out of pure imagination, the type of “right-brain” creativity that’s the complete opposite of the logical, analytical, “left-brain” thinking that I do in my day job.

And there are certainly costume designers that DO design that way – but I’m not one of them. I’ve worked with – and learned from – some amazingly creative designers whose ability leaves me in awe. My friend Lloyd was probably the most creative person I’ve ever known. He was able to start with piles of fabric, come up with ideas as he went along, and somehow have it all end up as a cohesive, beautiful product (he claimed, in fact, that costume ideas would often come to him in his sleep when he was working on a show).

I work in the opposite way. For me, designing costumes for any show is an exercise is analysis and problem solving, almost like a mathematical equation. In any production, the costumes have a job to do. In every scene, the costumes should be communicating information about the characters, the relationships, and the themes of the play – whether the audience is conscious of that or not. So my job as a designer is figuring out the most effective way for the costumes to do that job.

I start by identifying the “givens” of the production: When and where does the action take place? What is the time span of the events? What is the overall feel or concept of the production? Then, I consider the specifics of each character: what is this person’s life like? What is the character’s economic status, ethnic background, role in society? Next, I think about the relationship between the characters. Who is related to whom? Do different characters become closer – or more distant – over the course of the play, and if so, in which scenes does that happen?

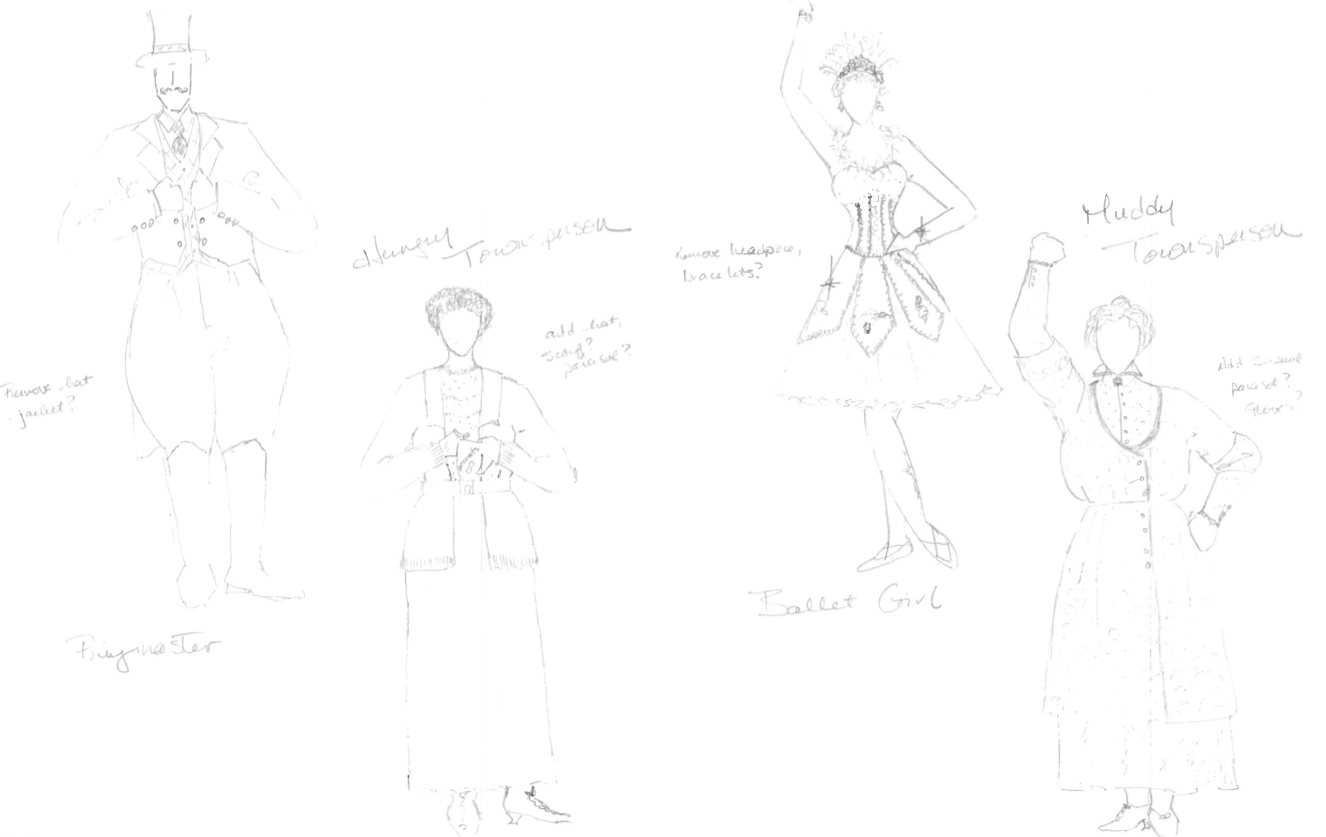

All of this analysis lets me plot out the job of the costumes – and frequently, I do plot out the relationships between the characters over the course of the different scenes on paper. When I have a good understanding of what the costumes need to do, I then decide how to use the different elements of design – color, line, texture, shape, and mass – to do it. I usually rely most heavily on color – it’s the element to which I react the most strongly, so I tend to use it for most of the heavy lifting. I may choose to have different colors represent different families or “teams” within the play, or to have a particular color represent an emotion, goal, or theme of the play. Here again, I often pull out a pencil and paper and chart out how the different colors, lines, and textures will be “assigned” to each character in each scene. Only when I have this general game plan can I make decisions as to what each character will wear in each scene – what are the clothes that will meet all of the requirements, to communicate the information about the character and relationships while also conforming to the time period, geographic setting, and overall tone of the production?

Because I work this way, I welcome the type of requirements that a more “right-brained” designer may see as limitations. One of my favorite plays to design was 12 Angry Men, which has some very specific requirements: the twelve characters have distinct personalities and points of view that have to be defined, but they are all in a setting – a courthouse -- where the social conventions of 1959 dictated that they would be dressed a particular way. Given that each character had to wear the same basic garments – shirt, tie, jacket, trousers, hat, and shoes – how can those garments be chosen to embody each juror’s character and underline the changing dynamic among them? It was a perfect design project for me.

For me, the design process is a lot like solving an acrostic, sudoku, or jigsaw puzzle (all of which I also enjoy). Or, in fact, like the type of analysis that I do every day at the bank. The audience may never be consciously aware of it, but when every piece of the costume puzzle falls into place, they all add to the cohesive whole of the production.